Film Matters is thrilled to reveal the winner of the ninth annual Masoud Yazdani Award: Cole Clark for his FM 13.2 (2022) article, “Afraid to Live, Afraid to Die: Sources of Anxiety in She Dies Tomorrow.” Cole is a graduate student at Chapman University pursuing a master’s degree in Film and Media Studies. He completed his BA in Film Studies at Chapman University, with a minor in English. He has presented on masculinity studies at the 2023 National Conference on Undergraduate Research, and film phenomenology at the USC First Forum 2023 conference. His research interests lie in the fields of masculinity studies, phenomenology, gender studies, and sound studies.

Our judges also wished to recognize Aatika Fareed with an honorable mention for her FM 13.1 (2022) article “Western Modernism and the Fetishization of the Hijab: Deconstructing the Movie Hala.” Aatika is a senior at Indraprastha College for Women, University of Delhi, majoring in History and English Literature. She hopes to combine both of these disciplines in order to explore the impact of literature and media in defining historical events, current political scenarios, and collective mentality. In addition to this, she is an avid writer and has recently contributed as a short story writer for two anthologies published by Swadhya Publishing House, Select Short Stories: An Anthology (2020) and Swadhya Micro Stories (2021).

We are grateful, as ever, for the work of our volunteer judges, who identified our two honorees after a rigorous judging period last fall:

Lexi Collinsworth, a master’s student in Film Studies at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, treads the delicate intersection of dance and cinema. In addition to her academic pursuits, she founded “Dance on Film” at UNCW, offering guidance to undergraduates while fostering an appreciation for interdisciplinary art. Beyond the academic sphere, Lexi runs a photography business known as “The Reel Shot,” specializing in portrait photography. This November, a collaborative effort materialized in the form of her codirected short dance film, Reflections in Motion, premiering at the Cucalorus Film Festival. Lexi remains dedicated to pushing boundaries, aspiring to weave genuine, unassuming stories within the tapestry of contemporary cinema.

Hannah Davenport is an aspiring film scholar currently located in Wilmington, North Carolina, where she attends the University of North Carolina Wilmington as a Film Studies graduate student. Her academic interests include regional American cinema and ideological film criticism, as well as aesthetics and phenomenology. Outside of class she spends her time reading and watching “bad” movies.

Dason Fuller is a graduate student pursuing his MA in Film Studies at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. He received his BA in Film Studies in the summer of 2023, and has two upcoming published pieces appearing in Film Matters in the spring of 2024. After achieving his MA, Dason is interested in pursuing academic writing and teaching.

Clayton Sapp is a master’s in Film Studies student at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. His research primarily focuses on masculinity and romance in popular Hindi cinema. When he is not engaged with his research, he can be found volunteering at local nonprofit film organizations, or at a coffee shop grading papers for the class he assists in teaching.

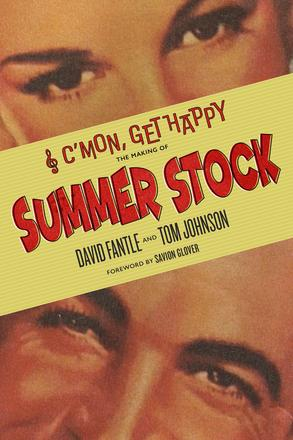

Each year Film Matters – in fond remembrance of Masoud Yazdani, founding chairman of Intellect and a key person in the establishment of our journal – revisits the peer-reviewed feature articles from the prior volume year with the help of graduate student judges. We approach this with enthusiasm, an opportunity to celebrate the innovative and passionate texts we publish, products resulting from the unique collaborative work of emerging undergraduate film scholars, their mentors, and the Film Matters publication process. The honorees receive book awards from the field of film studies, in recognition of their achievement. For more information, please visit: https://www.filmmattersmagazine.com/masoud-yazdani-award/