Sophia Stolkey: In the beginning of the book, you set out to shed light on the underrated film musical that is Summer Stock and “elevate” it to a higher standard of renown. Could you tell readers a little bit about why this film tends to be overlooked in the canon of Hollywood’s Golden Age from your perspectives, and why it deserves greater attention overall?

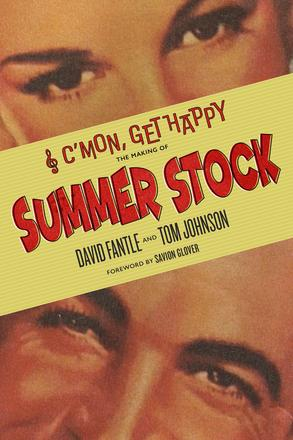

David Fantle: As for why it doesn’t get as much attention, and why it’s not in the same conversation as Singin’ in the Rain, or Easter Parade, or those great musicals, I think one reason is that the plot is a bit trite. You know: “Let’s put a show on in a barn…” It’s a little bit of a throwback to films that Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney were doing ten years earlier. But we thought the film was worth closer examination because after writing about it and screening it many, many times, what we’ve realized in audiences we have watched it with is that in the 109-minute runtime, there’s arguably more outstanding musical numbers in those 109 minutes than any of these aforementioned “classic” musicals that are always talked about. We have Gene Kelly’s all-time favorite dance number with the squeaky board, Judy Garland’s iconic swan song to MGM, “Get Happy.” We have “Dig-Dig-Dig Dig for your Dinner,” a terrific tap number. We have arguably the best dance duet that Gene and Judy did out of the three films they worked on together. So, minute per minute, number by number, we think this film has so many showstoppers.

Tom Johnson: What drew us to this, too, was the backstory. There was so much drama in getting this made; it was Judy’s last film at MGM. After fifteen years of work at MGM, the only studio she ever knew, she parted with them right after this movie. And as Dave said, it was sort of a trite plot — no one wanted to do it. Gene, Judy, director Chuck Walters, they were all trying to get out of it. But they all came together as sort of a security blanket for Judy Garland, because she was really up against it with her drug dependencies, raising her daughter Liza pretty much as a single parent, and all these things she had problems with at the time. So they surrounded her, the professionalism was there, and they got the thing done, which was just amazing. And what you see in the numbers, and especially in some of the dramatic scenes, is the real feeling that Judy and Gene had for each other. There’s a real love there. It wasn’t even really acting — you could just tell. And I don’t think that exists in any other Judy film, where you see that real regard for each other, and love for each other.

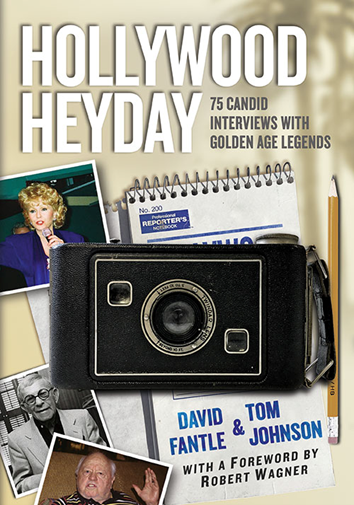

SS: You both have been talking about this era of film history and interviewing artists for a long time. You write about how this project was decades in the making, with material taken from interviews you both did with big players at MGM in the late 1970s and early 1980s. How has this project taken shape over time for you?

DF: Well this is actually our fiftieth year as not cowriters, but friends on this classic film journey. It started fifty years ago when we were fifteen years old and saw the film That’s Entertainment! in 1974. We got hooked on the classics — musicals particularly, but all the Golden Age films. So, in some respects, when Tom and I say this book was forty-five years in the making, we say that because, in 1978, when we were just out of high school and about to start at the University of Minnesota, through a lot of tenacity, chutzpah, gall, nerve (whatever you wanna call it), we had greenlit visits from Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly. So Tom and I, when we were eighteen, hopped on an airplane from Minneapolis (which is our hometown) and had these transformational meetings with them. That led to hundreds more interviews with Golden Age stars, directors, and songwriters. But during the course of these interviews, Tom and I interviewed Charles Walters (the director of Summer Stock), costar Eddie Bracken, Harry Warren (the principal songwriter), and Gene Kelly. We didn’t know forty-five years ago that we would end up writing a book in 2023 on Summer Stock, but we were at least intuitive enough to ask them some questions. So we had some questions, we had some tapes, we had our taped archives and transcripts, and we were able to put some of that first-person primary research that we did years ago into the book. But we actually put the pedal to the metal on the book in 2019. We spent pretty much the entire pandemic researching, doing Zoom interviews with celebrities who are part of the book, and, of course, writing and going through the publishing process.

TJ: We were very conscious while doing primary research. We had a lot of archival research and information from people who were involved in the film — mostly all deceased, of course, now. But we were really determined to think about how we could take a contemporary look at a film that was made in 1950. So, during our research and creation of the book, we had Savion Glover—notable Tony-award winning choreographer and dancer—write our foreword. We talked to contemporary dancers, choreographers, and artists like Mikhail Baryshnikov, Ben Vereen, Lorna Luft (Judy Garland’s daughter), Tommy Tune, and Michael Feinstein. And talk about topical: in the book, we have a breakdown of a lot of the dance routines in the film from choreographer Mandy Moore, who has choreographed the modern film musical La La Land (2016) and, most recently, the “I’m Just Ken” number from the Oscars ceremony, which pretty much stole the show! So, Mandy was terrific in offering contemporary insights into a film that’s now around seventy-five years old.

SS: The book’s epigraph is a quote from Gene Kelly during his acceptance speech for the AFI Life Achievement Award. The quote reads, “I’d like to say one word about the people the public has never seen who knocked themselves out so we could look good. No one knows their names!” There seems to be a rise in demand for recognition of those who work behind the scenes in the industry, from last year’s SAG-AFTRA strike to more acknowledgement of backstage labor throughout this year’s awards season. What were some of your biggest takeaways from exploring the lives and impacts of those who labored off-screen to make Summer Stock?

DF: I think the most telling revelatory moment was our deep dive into the film’s producer, Joe Pasternak. Joe Pasternak was the #2 producer of musicals at MGM, after Arthur Freed, and we were able to talk to his son and actress Connie Francis and get some insights on a man born in Hungary who was known for his musicals with happy endings. That was his whole mantra — he wanted people to go into the theater and leave with a smile on their face. But it hid a tragic backstory of Pasternak’s personal life. He lost his father, his sister and brother-in-law, their children, and dozens of other relatives, while he made every effort to get them to the United States. But they all perished in the Nazi death camps. But that did not change his philosophy of wanting to entertain people with musicals that had happy endings. And Connie Francis, who was in the later Pasternak production Where the Boys Are and who became really good friends with him, said the only times ever she saw Joe Pasternak cry were when John F. Kennedy was assassinated and when he would talk about the Holocaust. It’s a deeper dive into a major player in Hollywood who most people don’t know anything about.

TJ: Yeah, the people behind the scenes were not below-the-line people. They were pretty much above-the-line. Charles Walters was fantastic—we interviewed him out in Malibu in 1981, and by then he was retired. He was one of Judy’s best friends, throughout her entire life. He danced with her in a couple of her earlier on-screen musicals. He directed Barkleys of Broadway, Easter Parade, all these great musicals. But he said working on Summer Stock gave him an ulcer. It was just so tough getting through that shoot…trying to keep Judy motivated, on-key, and focused. But he was known at MGM for bringing in musicals either under-budget or on-budget. So the studio’s head office loved him. The only time in his career that he went over anyone’s head (at least up until that point) was actually during the shooting of Summer Stock. He wrote this memo to Dore Schary (then VP of production at MGM) asking him to reconsider the film, and Schary basically told him, “you’re stuck with it.” He possibly blew it by misspelling Dore’s first name, though.

DF: Yeah, don’t spell your boss’s name wrong, right? . . . But the book explores how he had to play part-psychologist, because he knew when Judy was up, when she was down, and how to work with her regardless of her personal situation. He knew when he could motivate her, when he couldn’t, and what to do during those down times. It caused him an ulcer, and a massive cigarette-smoking habit, but he knew how to work with her. And he loved her, too.

TJ: And Judy would see through bullshit. She had a bullshit meter that was very acute. So Chuck knew that he couldn’t just jolly her in synthetic, fake ways. He basically knew what little things he could do that she would respond to.

DF: By 1950, the studio system was starting to slowly collapse, because of the advent of television and other factors which are covered in the book. So, MGM executive Dore Schary came in realizing that the bottom line was what it was all about for shareholders. So that’s why he wasn’t a big fan of “coddling” the high-priced talent, and wasn’t nearly as empathetic to Judy’s situation as someone like Louis B. Mayer actually was.

TJ: And Louis B. Mayer knew Judy from the beginning, and that’s why he didn’t want to bounce her off the film when she was having problems, because he said that Judy made this studio a fortune in the good old days, the least we can do is stand by her now.

SS: The studio system during Hollywood’s Golden Age, though it generated so many iconic films, in hindsight may have been a bit brutal for its treatment of stars and other players. The “maddening dichotomy” of the film’s production versus its affect remains. How do you reconcile the joyful exuberance of the film itself with the troubles that pervaded its creation and its aftermath?

DF: I think making art is sort of like making sausage. You don’t necessarily want to look at the process, you just want to look at the end result. So to think there wasn’t some tension on set while they were creating art would be naïve. Were there personality clashes in the Golden Age? Of course. Were there issues? Of course there were. I think it just sort of went with the territory. The studio system certainly had pros and cons, but if you talk to most of the stars who were part of it—and we’ve talked to a lot of them—they would never have traded it in for the post-studio environment that now exists. Debbie Reynolds told us, “where else can you get dancing, singing, acting lessons?” They took beautiful photographs, they had a publicity machine that was unparalleled . . . they were star-makers. And sometimes the studio system can be criticized, and there are certainly aspects to criticize. But I don’t think there are certainly more aspects to criticize than the current state of Hollywood production.

TJ: Back seventy-eighty years ago, was there sexism? Yeah, absolutely. And that’s come up a few times—Gene Kelly has been shredded a little bit for his “alpha-male” behavior. Even in the book, there are some run-ins he has with Nick Castle . . . you know, big egos and perfectionism. But you don’t get quality films like An American in Paris, Singin’ in the Rain, or Summer Stock without being a little tough. He knew what he had to do, and he didn’t suffer for it, so he can come across a little tough. But as Dave said, the proof is in the pudding—the legacy that we have of all of these great films and what went into making them—it wasn’t pretty a lot of the time. At the end of the book, we quote Liza Minnelli talking about her mother Judy, saying that there were tough times but it was “straight up all the way.” And that was the way it was—ultimately, they had to come through. They had to be great. They couldn’t take shortcuts, especially not Chuck, Judy, and Gene.

DF: In 2024, there seems to be a bit of a negative connotation around the word “perfectionist,” and we’re not exactly sure why. Because Gene Kelly and these artists of that magnitude at the time did not expect anything from their co-stars that they didn’t expect of themselves, times five! If they didn’t have that perfection, we wouldn’t even be talking about these films. What makes these musicals enduring works of art to this day is the perfectionism of the artists associated with them. Times have changed, times are different, and as Tom alluded to, the sexism, the casting culture . . . it’s not a revelation that it existed from the earliest days of Hollywood all the way to Harvey Weinstein. It permeates all aspects of American capitalist society.

TJ: Not great, you know, we’re not trying to soft-soap it. It just sort of was the way it was back then. We interviewed a lot of MGM ladies— Kathryn Grayson, Ann Miller—but they all said they loved that studio system. Some of them kind of bridled against it, but almost all of them said that they felt protected most of the time. And then it just went away, and after being groomed to be part of this family of sorts, they had to figure out a way to proceed individually with the rest of their careers. A lot of the MGM ladies we interviewed, and Kathryn Grayson especially, bemoaned the fact that the studio system just went away.

DF: We also don’t want to lump the studio system under one umbrella. MGM under Louis B. Mayer had its own culture. Warner Bros. was a different culture under Jack Warner. Universal under Laemmle was a different culture. Fox under Darryl Zanuck was a different culture. While there were several major studios, the working environment at each of these was different.

TJ: Harry Warren (the main songwriter for Summer Stock) mentions that MGM was different. He said that anywhere else, Judy would’ve been fired for missing so many days of production. But at MGM, she was huge, a star. Even when Warren was writing his songs, he said it was like a country club at MGM compared to Warner Bros. It was just easier. But like Dave was saying, it was just different at every studio, and you just had to feel your way around to get a sense of the cultures.

SS: In the book, you and several interviewees talk about Judy Garland as a performer often in terms of her vulnerability, both on-screen and off. Later in her career, the roles she took on seem to showcase her vulnerability quite literally, reflecting her own journey and challenges as an artist still struggling to live life on her own terms in the wake of a childhood taken over by MGM (the studio where she worked under contract since the age of thirteen). What was it like writing about Judy’s role/performance in Summer Stock in relation to writing about her personal life, and how did you approach the task of weaving those together?

DF: We wanted to take a real empathetic approach as to why Summer Stock was a troubled production, and we go into detail as to why it was beyond some of Judy’s issues. But you mention Judy’s roles—there’s a couple of things that maybe we don’t emphasize enough in the book. If you look at so many of her hits prior to Summer Stock—whether it was In the Good Old Summertime, Easter Parade, The Harvey Girls, The Pirate—these were all period pieces. In Summer Stock, you had a contemporary story in the 1950s, but you also had Judy Garland playing a strong, independent woman. When her hired hands leave her character at the beginning of the film, she’s left with her friend and assistant (played by Marjorie Main) to figure out how she’s going to get the crops in. She certainly stands up to Orville, Eddie Bracken’s character. But I think that’s a little bit of a hidden aspect of Summer Stock that people never really examine.

TJ: Also, a lot of contemporary reviews mentioned her weight. You can consider that, especially when you see her perform “C’mon, Get Happy”at the end, and she’s so slim. Filming had wrapped, then she came back three weeks later to shoot this number, and she had lost all this weight. That was just a real juxtaposition for people. But Dave and I always thought she looked healthier in Summer Stock than she had in her three or four previous films, where you could have lifted her up with one hand.

DF: It is somewhat sexist—why did they pick on her body type but not Phil Silvers’s body type, or anyone else in the cast?

TJ: But eighty years ago, that’s what they did. A lot of female stars had a tougher road. Even today, it hasn’t changed that much. The optics mean a lot, and guys get a pass.

DF: That was the norm. And it still is somewhat the norm.

SS: You also write in your book about how Judy didn’t have a strong belief in herself. But she was able to find strength in bringing joy to people, hence the title of the book.

TJ: Right, C’mon, Get Happy, which is a bit ironic. Katharine Hepburn once told Judy, “you’re one of the greatest actresses I’ve ever seen.” But as Chuck Walters said, Judy would’ve killed to be Lana Turner, to be gorgeous. No one had what Judy had—the voice, the acting, she was an absolute wunderkind. She was amazing, but she didn’t value any of that. She would have traded it all to be Marilyn Monroe.

DF: Certainly, we left the entire Judy story to other biographers who have extensively covered all aspects of her life. But we give a flavor for her life, and certainly the relevance of what was going on in 1949 and 1950, around the Summer Stock period, which we take a deeper dive into.

SS: I loved reading about Charles Walters—a director who didn’t garner as much attention as some of his contemporaries, but who churned out films with both great efficiency and artistry, also informed by his experience as a dancer and choreographer. How does his role as director of this film inform your view of Summer Stock as a pivotal turning point in the way major studios were functioning and making their musicals?

DF: Well, when you look at Summer Stock, it had about a six-month production window, which in today’s world seems pretty short. But by MGM standards, it was really long. All the other musicals were generally taking two-three months, but miraculously, even though it was six months in the making, it was barely over budget. So that’s a testament to Chuck Walters. But I also think when you look at musical films, and you look at the great directors—Vincente Minnelli is usually cited as number one. You have people like Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, Chuck Walters, and even George Cyndi. But musicals are multidimensional, complex films. You have a storybook, recordings, dubbings (the dancing and singing is all done to playbacks), so there’s so much intricacy in making a musical that a lot of people don’t fully appreciate. Someone like Minnelli was filming the entire book sequence, but you had Gene Kelly who was also starting to become a director in his own right. You had someone like Gene Kelly who could actually take the helm of the musical numbers. And that was true with Chuck Walters, too. Chuck was so multidimensional because of his background as a choreographer, director, and dancer, that he could be behind the camera directing every component of the film. The last number that was shot for the film was Gene Kelly’s solo dance number with the squeaky board—his all-time favorite solo dance routine throughout his career. And again, cobbling together what we could from our research, Chuck had already closed down production and moved on to another project at this time. But Gene had co-directed his first film On the Town prior to Summer Stock, so our book goes into the theory that for the squeaky board number, Chuck wasn’t behind the camera at that point. It probably was Gene Kelly behind the camera for that routine.

TJ: Chuck choreographed the “Get Happy” number. He actually performed the number for Judy when she came in to shoot it. One of the dancers had said Chuck was a great aper—he could ape anybody. One of the best testaments to Walters’s direction of dance numbers is the number “Dig-Dig-Dig Dig for Your Dinner” and the way that the camera follows Gene 360 degrees around the table. That’s a real Chuck Walters thing. I don’t think Vincente Minnelli would’ve been able to do something like that, it wouldn’t have occurred to him. But with Chuck, the camera is dancing along—it never loses sight of Gene coming around and going up and down that table. And he knew how to camera cut to the music, to the number, because as Dave said, he was a choreographer. So, he got it, he understood, he had a dancer’s sense of what needed to be filmed and how it needed to be filmed.

DF: But he also had a good eye for scripts as well. Because as we go into detail in the book, the script was significantly larger than the actual shooting script. There was a lot of over-the-top comedy schtick. Fortunately, Chuck had the good sense to look at these earlier versions of the script and, although he had misgivings about the story itself, he had the good sense and taste to excise pages of this over-the-top comedic schtick that we don’t think would have added any value to the film.

SS: Are there any further or future projects either of you is working on at the moment? Anything that your work on Summer Stock has inspired you to start tackling next?

DF: We are in year two of research for another musical-related book.

TJ: We can’t get into the title.

DF: It’s not Judy and it’s not Gene. But it’s a book about a production like Summer Stock that may not be on the tip of people’s tongues, but has a lot of interesting story angles. We can’t say anything more right now, but we hope to get that written and published in the next two-three years.

C’mon, Get Happy: The Making of Summer Stock is available now from University Press of Mississippi.

Author Biography

Sophia Stolkey is a recent graduate of Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, and will be pursuing a master’s at the University of Southern California’s School for Cinematic Arts this fall. Her main interest lies in mapping functions of memory and sensation in relation to one another, both on and off the screen. Some of her favorite films tend to center childhood experience, forces of nature, and dreams.