One of the most undervalued films of the last twenty years is Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers (2003), a masterfully wrought picture that serves, in equal parts, as a panegyric on the power of cinema and a warning to those who abandon that power in pursuit of pure aesthetics. The film, set amidst the popular riots that swept through Paris in 1968, follows the hedonistic sojourn of three young cinéastes: Matthew (Michael Pitt), a young American studying in France, and Theo (Louis Garrel) and Isabelle (Eva Green), a set of Parisian twins whom Matthew meets and befriends at the Cinémathèque Française. Despite the turbulent, historic backdrop of the film, however, Bertolucci largely ignores the rioters; instead, the camera’s gaze is directed toward the three characters who, despite professing an ostensible solidarity with the ideals of the revolution, increasingly withdraw into a sequestered and sybaritic world of their own creation. And it is in this dissonance–between the power of ideas and the sterile, indulgent lives of those who hold them–that the true beauty of the film shines through.

Indeed, the film is exceedingly beautiful. In the penthouse where the trio squander their days, the scenes are inculcated with a saccharine sentimentality and a muted, ethereal beauty. As the twins, whose parents have left on summer holiday, invite Matthew into their world, we as the audience are gradually drawn in with him. And in this world, replete with decrepit walls, posters of various ideologues and campaigns, and an eclectic assortment of statues, records, and discarded wine bottles, the characters can escape the repressive mores of society and into an Eden of their own construction.

For many viewers, however, the world that Bertolucci constructs seems to be one, not of beauty and refinement, but of stale ostentation and threadbare cliché. Matthew, Theo, and Isabelle spend much of the film lounging around the flat, naked or nearly naked, debating Maoism, quoting Cahiers du Cinema, and amusing themselves with fleeting pantomimes and tableaux of famous movie scenes. These discussions, although treated with a solemn, youthful earnestness by the young protagonists, nevertheless feel quixotic and overly nostalgic. The dreamers seem trapped in the metaphysical conceits of the cinema, divorced from reality, and existing in a sort of liminal space between idealism and banality. And this effect is only heightened by Bertolucci, who injects sequences from classic films–sequences which are often pantomimed by the characters–into the diegesis.

It is easy, then, to view The Dreamers as Bertolucci’s contrived, heavy-handed homage to cinema. After all, Matthew, Theo, and Isabelle represent archetypal cinéastes. They can quote the canon of cinematic scholarship. They spend their days debating the respective merits of Keaton and Chaplin. Even some of their experimental sex acts, which span from the tender to the aberrant, are initiated when one of the characters fails the game of cinematic pantomime that they play numerous times throughout the film. In short, the movie seems to be the ultimate cinematic tribute: three cinephiles, possessed by a love and passion for the movies, united in a cramped, messy Parisian flat. It’s hardly surprising that some viewers felt the film to be forced and affected.

Such a reading, however, while understandable, also seems to oversimplify the beauty and nuance of what Bertolucci has accomplished with The Dreamers. After all, as the title suggests, Bertolucci sets out to construct a dream. The mise-en-scene of the apartment, imbued with the dim light of lamps and candles, is cluttered with a synesthetic medley of art pieces, decorations, and the refuse produced by the insouciant escapades of the dreamers. Together, these elements converge to lend the apartment a dreamlike quality. The setting, rendered perpetually nebulous and incomprehensible by the vast profusion of visual stimuli, serves as a beautiful limbo where the trio discusses and debates (but never acts upon) profound ideals. In short, the world of the dreamers is one of emulation, digression, and impotent exploration. It is an onanistic environment where the characters mimic greater ideals (either through their literal impersonation of movie scenes or their debates about film, political, and cultural theory) without ever embodying them.

Nowhere is this ostensibly empyrean world, this journey into a state of unbridled indulgence and excess, more vividly displayed than in the moments before Matthew, jettisoning any lingering doubts he has about the twins’ irregular existence, takes Isabelle’s virginity. After all, Matthew’s consummation of his new friends’ lifestyle begins, rather ironically and abruptly, with a death. This is not a literal death, however, but rather Theo, playing the game of pantomime that the three characters amuse themselves with numerous times throughout the film, reenacting a death scene from Howard Hawks’s Scarface (1932). As Theo falls, clutching his throat and gasping in crude charade, his shadowy form seems to blend with the dappled chiaroscuro of the carpet. Unable to guess the scene, Matthew and Isabelle are forced “to pay the forfeit”: they “must make love in front of [Theo].”[i] And in this moment, as if the characters have reached the metaphysical apogee of their epicurean exploration, Bertolucci imbues these scenes with a strange, oneiric quality.

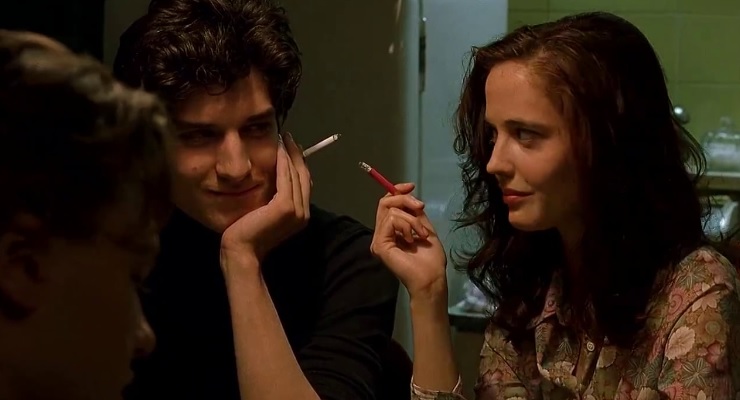

Indeed, as the challenge is issued and the stage is set, this scene, through its dim lighting, muted and golden colors, and carefully selected source music, seems to possess an air that is equal parts surreal and sublime. As the three characters sit, smoking cigarettes, drinking wine, and arguing about the legitimacy of the challenge, their dancing shadows and subdued forms seem to meld and blend with the detritus and wreckage of the surrounding room. This unkempt atmosphere, which would otherwise seem repugnant and pathetic, takes on a spirit of liberation when accompanied by the dim lighting of the scene. After all, the lighting, which dampens the potential abrasiveness of the moment, engenders a sort of suspension of disbelief in both the characters and the audience– as if the scene, inculcated with a synesthetic “flux and… eternal recurrence,” marks Matthew’s transition into some transcendent, isolated realm.[ii] This effect is only heightened by Isabelle who, as she removes her clothes, puts on a recording of Charles Trenet’s “La Mer.” Contrary to the potential for diegetic music to act as a “[strong] narrative intrusion,” this moment instead lends agency to Isabelle; by playing the piece, she and Theo are able to imbue their own world with refinement, casting a beautiful, aural integument over the proceedings.[iii]

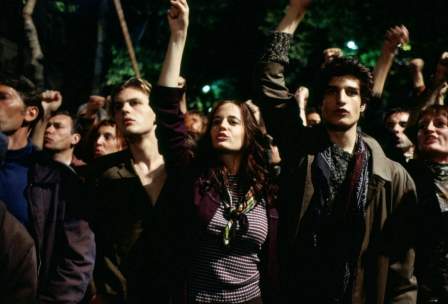

The ultimate irony of The Dreamers is that this ethereal, inconsequential space that the main characters inhabit is set against a series of historical events that proved to be enormously significant–particularly for the world of cinema. In the protests following the firing of Henri Langlois, the chief champions of the cinema–among them directors, actors, bureaucrats, and mobs of ardent cinephiles–found the chance to make bold declarations about the future of film as an art form. And yet, while debates raged in the newspapers and agitation embroiled the Parisian streets, Bertolucci’s muses (or perhaps anti-muses) remain sequestered in their house. The few times that Bertolucci directs the camera to the commotion beyond the walls of the flat the shots–often paralleled by illustrations of the aberrant, abject lifestyle of Matthew, Theo, and Isabelle– remind viewers that a real world exists beyond the fantasies of the dreamers. And through this dissonance–between the dreamlike and the real, the hollow and the consequential–Bertolucci turns the three characters themselves into a sort of conceit. Indeed, Matthew, Theo, and Isabelle serve as exemplars of the fate of those who worship autotelic aesthetics, who apotheosize form over content, who fall in love with the idea of cinema–all the while missing its true power to affect change.

Author Biography

Jake Dyson is a junior at Georgetown University where he studies Government, English, and Film and Media Studies. His film studies largely focus on cinema communities, relationships between films and audiences, and the confluence of auteurism and postmodern theory. He lives in Rochester, NY, and enjoys exploring the city’s rich cinematic history.

Notes

[i] The Dreamers, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci (2003; Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2004), DVD; 48:17.

[ii] William Miller, The Anatomy of Disgust (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998), 106.

[iii] Claudia Gorbmann, “Narratological Perspectives in Film Music,” Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1987), 25.

Film Details

The Dreamers (2003)

Italy

Director Bernardo Bertolucci

Runtime 115 minutes