An encounter with the unknown evokes two separate but equally powerful spheres of emotion: fear and fascination. In the film Arrival (2016)by Denis Villeneuve, linguist Dr. Louise Banks (Amy Adams) is tasked with peacefully bridging the dangerous gap of language between humans and the existentially threatening aliens— named heptapods—that have just landed on Earth. The tension between the two parties is immediate: military outposts, constructed within hours, surround the heptapods’ monolithic ships. Everyone, from the characters to the audience to the film’s poster, is haunted by the same question: “Why are they here?” Louise and her team of scientists, witnessing the aliens within the ship—massive, tentacled deep-sea creatures speaking in pulsating whale calls—find themselves at once terrified and deeply invested in decoding the heptapods’ movement and language. The barrier of mutual understanding in encountering something entirely foreign bars both empathetic communication and material self-evaluation. Yet, as powerful a force as Louise’s fear may be, her fascination with what is unquestionably deemed “other” drives her to make first meaningful contact with the heptapods. This same liminal conflict between repulsion and attraction is what defines early experiences in childhood, including and especially those with film, which not only serve as a demonstration of this contradiction, but a resolution of it.

Film phenomenology, a well-studied branch of film theory, offers a broad theoretical framework in film studies by focusing on the overall experience of film watching, considering the film a “phenomenon.” Unlike traditional approaches to film theory that may focus on the film as the main object—notably its narrative, technical aspects, or stylistic elements—a phenomenological approach to film explores the reciprocal relationship between film and spectator, lending appreciation to the spectator’s senses.

Further down that same field of study, filmic identification, a narrower yet equally well-studied branch of film theory, examines how viewers project themselves onto or see themselves within a film. This form of identification goes beyond merely enjoying a movie; film serves as a mirror upon which the characters, narratives, or cinematography reflect aspects of the audience’s desires, identity, or experiences.

In his contribution to film theory, French film theorist Jean Pierre-Meunier bridged filmic technique with filmic identification in his 1969 publication The Structures of Film Experience, wherein he introduces what is by far his most influential contribution: three distinct modes of filmic identification, loosely corresponding to three basic genres. In these genres, viewers engage with the film on different levels of recognition and emotional investment. In fiction, he claims that viewers have a voyeuristic distance; in documentary, a stronger but incomplete understanding; and in film-souvenir, loosely translated as “home movie,” a very literal self-identification. In Meunier’s home movie, we identify with the person whom we know on the screen, aware of both their recorded presence in front of the camera and their absence in immediate reality.

Other film theorists have translated and redefined the concept of film-souvenir to expand beyond its genre definition. In her article “Toward a Phenomenology of Nonfictional Film Experience,” Vivian Sobchack applies film-souvenir to our broader understanding of the way films evoke personal experiences and memories without explicitly depicting them. In this way, Sobchack relates film-souvenir less to direct identification and more so to parts of our lives that films mirror or represent. She attributes this effect of films to a state of dual awareness viewers have of both the constructed nature of film and the reality that it cannot entirely capture. “For a moment, in the midst of fiction, we find ourselves in the mode of documentary consciousness: looking both at and through the screen, dependent upon it for knowledge, but also aware of an excess of existence not contained by it,” Sobchack states (246). It was with Sobchack’s definition in mind that we decided to revisit two films that were in some ways incomprehensible in our childhoods and adolescence.

***

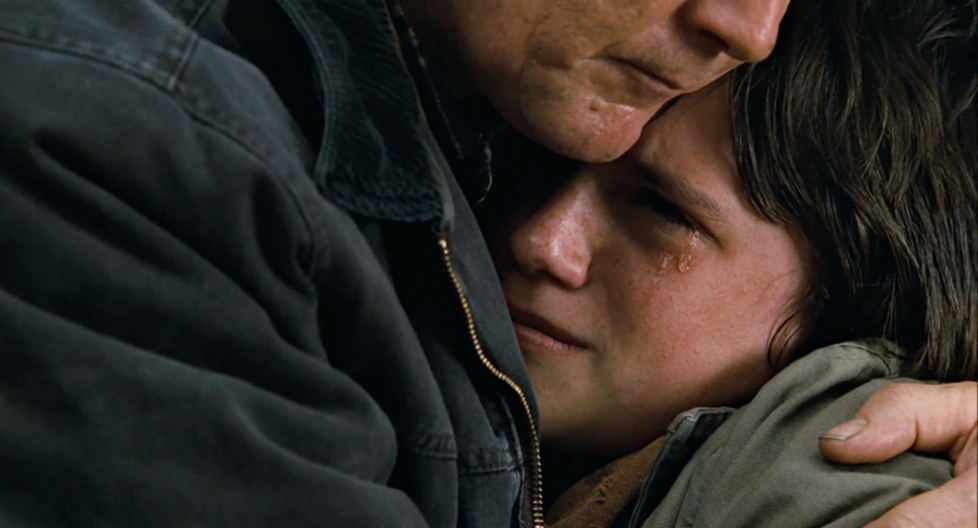

Bridge to Terabithia (2007) is a film we both watched in elementary school. Though the adaptation, based off the novel written by Katherine Paterson, is aimed at a younger demographic, it touches on various mature and emotionally charged topics, including poverty, gender roles, bullying, and most notably, grief. The film follows two childhood friends, Jesse (Josh Hutcherson) and Leslie (AnnaSophia Robb), who find solace in each other and in their shared vivid imaginations, until one abruptly dies by drowning. What stood out to us the most when trying to remember our experiences with this film is that we could only recall the film’s most traumatic moments.

***

Kai: I remember the classroom being disordered. Not many were paying attention to the screen, even when their fantasies turned into CGI spectacles. It was only when the film’s tragedy began that the class decided that the film was something worth paying attention to. Though I can’t speak for my peers, I found myself unable to understand the deeper emotions driving the character’s actions, and yet, I still felt something. I could understand that the characters in the film were sad. They cried like my brothers cried. They were mad like how I’d been mad. But there was something else behind those emotions that I couldn’t comprehend, and that was the why. I was emotionally affected by the symptoms of a diagnosis I was too young to understand, faced with questions I had no answers to, and without the life experience to be content with that.

Gillian: While I don’t remember the experience of watching the film with my classmates, I do remember the aftermath of talking with my friends about it and how my entire perception of the film was reduced to Leslie’s death. Despite having read the book beforehand, I took the loss of Leslie quite personally. Perhaps I wanted to “be” her in some ways, yet couldn’t grapple with that yet, so that when I felt both hollow after Jess’s parents informed him and, in a way, like Jess, distrustful. Other than Leslie’s death, I don’t remember many concrete things about the movie besides its more abstract details, like the rain and frayed rope, feeling their literal and emotional significance but being unable to interpret their symbolism.

***

Surprisingly, the aspects of the film that are ideally the most appealing to children, being the exploration of imagination and fantasy, are almost entirely left out of our remembered experiences of the film. Something just beyond our sight compelled us to feel emotions we weren’t ready to digest, and maybe that’s why we weren’t at first compelled to seek answers. Many years later, we both saw the film Arrival, both in our early adolescence, and both with our parents. Unlike Bridge to Terabithia,Arrival is explicitly a film for adults. Whatever existential questions Bridge to Terabithia poses, Arrival expands on tenfold, demanding one’s attention to them. But still, we were too young.

***

Gillian: When I watched this movie with my parents for the first time, I was pulled in by its spectacle and science fiction elements, which were equally familiar and unknown to me. I relate this experience in some ways to Roland Barthes’s attention to the hypnotic nature of film and how my childhood experience with film consisted of a preoccupation with visuals (347). Maybe rewatching the film years later allowed me to be “unglued” from the film’s spectacle in a way that I could better comprehend or face its underlying themes, like the circularity of time, mortality, and predetermination that my thirteen-year-old self didn’t want to deal with more than I had to.

Kai: Like Gillian, I too was obsessed with the film’s aesthetics and scientific implications. I cared more to see the floating spaceships and deep-sea aliens than I did to witness Louise’s struggle to be an ethical and precise translator. Like in Bridge to Terabithia, I was caught off guard, almost disturbed by Arrival’s ending. I knew that the shallow-focused shots of Louise’s daughter running through the backyard and rolling Play-Doh and the way that the music swelled and wept were all trying to tell me something, because seeing and hearing them hurt. I was again being asked questions I didn’t know the answer to.

***

Vivian Sobchack, in another essay regarding Meunier’s film-souvenir, posits that a feeling of unease in home movies comes from self-uncertainty (210). When you are faced with a mirror image of yourself, or in our case, a character whom we can see ourselves in, you ask yourself the question, “Is that really me?” Sobchack argues that, inevitably, this question transforms into, “What really am I?” When rewatching Bridge to Terabithia, we felt the same hurt as we did in our childhoods. We felt the same awe as we did in our adolescence, watching the otherworldly spectacle of Arrival. But alongside those familiar feelings, we were brought back to moments of apprehension and shame, responses to revelations just beyond our grasp. Using Sobchack’s reinterpretation of film-souvenir, we can begin to reinterpret these memories, not as moments of immaturity or confusion, but as existential growing pains.

Viewing films through the frame of film-souvenir, we can more readily identify the aspects of a story or its characters that resonate with our own experiences. As each the oldest among our siblings, we were, in part, able to recognize the strained relationship between the brother and sister in Bridge to Terabithia. Jess’s little sister May Belle constantly wants to be involved in Jess’s life, to his equally constant annoyance. Only after Leslie’s death does Jess let his sister into the colorful imagination he’d once shared with Leslie—a display of both self-acceptance and vulnerability, which helps him to process his grief.

While neither of us has experienced an equivalent to Jess’s experience with loss, we both relate to the conflicting desire to stay close to and distance ourselves from our younger siblings. By recognizing ourselves in a certain film like Bridge to Terabithia, we can gain a deeper appreciation for our relationships and the emotional complexities they entail. In turn, film-souvenir helps us carry these new philosophies into our daily interactions with those who the films remind us of.

While Bridge to Terabithia urges us to confront the unknown or unconsidered through grief, Arrival, perhaps because of its aim toward a more mature audience, presents an entirely different challenge. Arrival initially rejects film-souvenir by distancing the humans from the aliens, with a literal screen between the scientists and the heptapods, between the characters and us. However, as Louise begins to translate the aliens’ language and, with that, their intentions, the film begins to reveal the heptapods as conscious beings worthy of being understood, possessing the emotional and intelligent marks of what so far has been deemed “human.” Louise is faced with Sobchack’s essential question: “What really am I?” Instead of existentially threatening the scientists by posing a danger to their physical existence, the heptapods challenge the scientists’ preconception of what a meaningful existence might be defined as. In this way, the film challenges us to treat what is considered as “other,” or fundamentally inhuman, as deserving of empathy, to seek to understand peacefully and compassionately the frightening other.

Relating this message to film-souvenir, along with the act of studying film theory itself,teaches us to approach our younger selves with that same empathetic goal of translation. Film-souvenir is then not only what you recognize in a film, but what you remember about who you were when you first encountered it. Like how films reflect parts of our lives back to us, our recollections of our former selves during these viewings reflect aspects of our worldviews and self-awareness that have shifted over time. Without the lens of film-souvenir, we could not have found out why the films were so emotionally affective, regardless of our initial inability to understand them.

Though a lack of in-depth understanding may seem to condemn an audience to an unfeeling distance from a film, children, even in unlearned youth, are not passive spectators of film. In the conclusion of his 1951-1952 lectures, subsequently published in Child Psychology and Pedagogy: The Sorbonne Lectures 1949-1952 as “Method in Child Psychology,” French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty stated, “Adult functions are already expressed in the child, but are not present in the same sense. It is analogous to a game of chess; all the pieces are there at the start yet the face of the game changes” (447). Children possess a rich emotional range and the ability to feel what a movie has to offer; there is a raw empathy in how a child views a film in that they cry because others cry. At the same time, they may lack the intellectual maturity or knowledge to properly process these emotions.

What is powerful, then, about film theory is that it allows us to realize what our younger selves could not. Applying the concept of film-souvenir, we are invited not only to uncover what a film communicates to us—its existential questions and proposed solutions—but also to articulate and dissect the emotions it evoked before we had the tools to comprehend them. As Merleau-Ponty implies through his favorite metaphor of a chess game, the emotional responses of a childhood past are not shallower than an adult present, but are rather clouded with a lack of intellectual understanding. All the “pieces” are there on the board, yet their meanings and implications shift as we mature.

Attention to film-souvenir is a kindness because it involves translating and making sense of your prior experiences. In rewatching a film, you encounter a past self, an “other,” that you then must extend kindness toward. This past self exists in a realm of partial understanding, one that requires our present selves to bridge the gap between what was felt and what can now be comprehended. This process reveals layers of our growth and changing perspectives, illuminating how films that once moved us continue to shape our evolving sense of self.

Engaging with film-souvenir transcends nostalgia; theory, in effect, pushes us to reflect on both the films and the contexts that framed our responses to them. Within this act of translation, there is an inherent empathy: by seeking to understand “why” a film resonated or did not resonate with us at a particular time, we validate our past selves as worthy of understanding, both despite and alongside prior confusion, ignorance, or the rawness of emotion. In this way, film-souvenir becomes a process of continuous unfolding, affirming that our understanding of ourselves, like film, is never complete but always in progress.

References

Arrival. Directed by Denis Villeneuve, performances by Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner, Forrest Whitaker, Paramount Pictures, 2016.

Barker, Jennifer M. “Cinema and Child’s Play.” The Structures of the Film Experience by Jean-Pierre Meunier. Historical Assessments and Phenomenological Expansions, Amsterdam University Press, 2019, pp. 304-318.

Baronian, Marie-Aude. “Remembering Cinema: On the film-souvenir.” The Structures of the Film Experience by Jean-Pierre Meunier: Historical Assessments and Phenomenological Expansions, Amsterdam University Press, 2019, pp. 218-228.

Barthes, Roland. “Leaving the Movie Theater.” The Rustle of Language. Translated by Richard Howard, Collins Publishers, 1986, pp. 354-349.

Bridge to Terabithia. Directed by Gábor Csupó, performances by Josh Hutcherson, AnnaSophia Robb, Bailee Madison, Walt Disney Pictures, 2007.

Hanich, Julian, and Daniel Fairfax, editors. The Structures of the Film Experience by Jean-Pierre Meunier: Historical Assessments and Phenomenological Expansions. Amsterdam University Press, 2019.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Child Psychology and Pedagogy: The Sorbonne Lectures 1949-1952. Translated by Talia Welsh, Northwestern University Press, 2010.

Sobchack, Vivian. “‘Me, Myself, and I’: On the Uncanny in Home Movies.” The Structures of the Film Experience by Jean-Pierre Meunier: Historical Assessments and Phenomenological Expansions, edited by Julian Hanich and Daniel Fairfax, Amsterdam University Press, 2019, pp. 205-217.

Sobchack, Vivian. “Toward a Phenomenology of Film Experience.” Collecting Visible Evidence, University of Minnesota Press, 1999, pp. 241-54.

Author Biographies

Kai Paschall is a senior undergraduate student at Hendrix College, where he is currently pursuing a BA in Film Studies while on a Pre-Med track. He hopes to maintain both a medical career and academic involvement with film. His interests include animation, experimental horror, phenomenology, video editing, and filmmaking.

Gillian Fast is a junior undergraduate student at Hendrix College, where she is pursuing her BA in Film Studies. She currently aspires to a career in multimedia or film journalism, combining her passions for storytelling and reporting with cinematic analysis. Her interests include cinematic realism, psychological horror, documentary filmmaking, and copyediting.

Hendrix College is a private liberal arts college in Conway, Arkansas.