The St Andrews Film Festival (SAFF), which took place 22-28 November 2021, celebrated its third year with a wide array of international films. Born in 2018 through the University’s Filmmakers’ Society, SAFF has become a charity committed to raising the profile of St Andrews and Scotland within the international film scene. Boris Bosilkov, Mina Radović, and Walid Salhab curated a fine week-long experience full of excellent films – from around the world and Scotland itself – accompanied by fascinating talks with the directors. But while the festival moving to a purely online format – due to the pandemic – allowed for an unprecedented degree of flexibility, it also limited the connection between filmmaker and audience that film festivals usually bring. Therefore, it was such a brilliant initiative by Boris to host talks on Zoom with some of the filmmakers, which allowed for lively Q&A conversations. With sixty films to choose from, this helped to draw attention to the more notable entrants. Rounding off the week with a Zoom-based ceremony with around twenty awards also helped unite the filmmakers and audience after the week’s uncharacteristic isolation, giving additional promotion for some remarkable films that would otherwise have been overlooked. The SAFF team did an excellent job crafting a platform for St Andrews, pushing the town as a hub for global cinema.

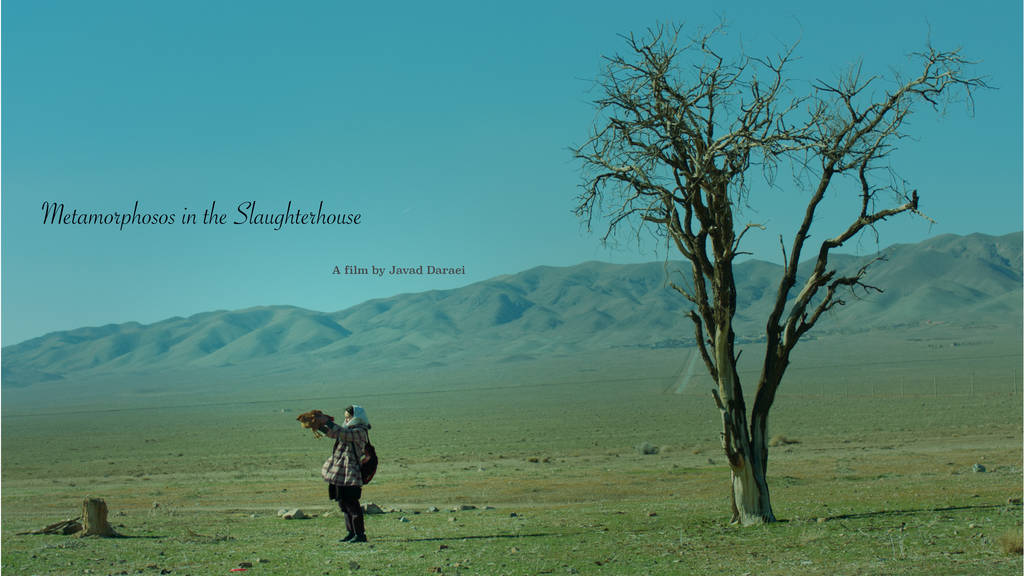

Metamorphosis in the Slaughterhouse (Javad Daraei, Iran, 2021) is a quietly tragic drama about a girl suffering the hate of her village for the death of another girl and won the Rosaura Revueltas Award for Best Actress for Sarina Yousefi. With slowly ramping tension, this is a strong film – although the tears are mostly provoked by a chicken being eaten, which the director later explained was his initial source of inspiration. Daraei’s filmmaking style is characterized by arid shots lingering on solitary figures, eliciting a wealth of emotions through the most miniscule of movements. Whenever the film shows dangers of feeling tacky, Daraei always re-energizes it with subtle explosions of color – especially of a lovely minty flavor that I rarely see on film – or by breaking his otherwise restrained cinematography with erratic camera movements amidst chiaroscuro lighting. The film looks and feels amazing, which is impressive considering the problems that arose when making it. Daraei spoke extensively about the challenges of filming in Iran, constantly facing trouble with the authorities and frequently getting arrested. This forced him to film in abandoned villages, recast actors who were informing on him, and even drastically censor his final work. This heightens the parallel to Kafka’s Metamorphosis the title suggests, as those Kafkaesque themes of lacking control over one’s own life are prevalent in both film and production.

Sarina Yousefi may have won Best Actress, but my personal pick would have been for Antonia Thomas in All on a Summer’s Day (Avril E. Russell, UK, 2020), a thriller about a woman whose car breaks down and a man who refuses to leave her alone. More established than most of the other actors, many of whom are making their debuts – she was in the TV series Misfits – Thomas stands out in this festival. From her initial contemptuous expressions at the start, to her unhinged terror as the film descends into horror, Antonia goes through a powerful, tear-stricken transformation. Jamie Sives is deliciously creepy, his uncanny kindness derailing the film into extremely uncomfortable – yet gripping – territory. In the Q&A, Russell asks “where [do] we draw the line of what we truly consider entertainment,” and the film’s exploration of this question makes it an incredibly powerful experience. It is seriously tense throughout, but while it is shot and edited well, there are many very strange moments that tarnish the quality. And this is because Russell’s film was, in a way, stolen from her. The editor cut it out of recognition, while locking Russell out of the raw footage. She tried her best to piece it back together, but some sequences remained rough, as she had to recreate shots using animation. As she admits, “there’s an odd, experimental feel… those are the scars… the manipulations to make the narrative hang together.” Russell shared how Quentin Tarantino “raved” to her about how much he loved the short film version – which inspired her to expand it into a feature – so it is a pity that this talented director had to overcome such a hurdle. But to have come out fighting is a great achievement, for which she deserves full recognition.

The winner of The Saint Andrew Award for Best Feature Film – as well as the Winston Ryder Award for Best Sound – was Speak So I Can See You (Marija Stojnić, Serbia, 2019). This is a remarkable achievement considering the film was not exactly planned, since Stojnić only made it after staying in Serbia for a year instead of the intended week. It was during this lost “dark time” that she began listening to Radio Belgrade, with its curated program of history, culture, art, and philosophy, mostly from the “golden age of Yugoslavia… the 70s and 80s.” This fundamentally changed Stojnić’s perception of her unfortunate situation, connecting her to the city and its people, which she sets out to explore. The result is a film based on Radio Belgrade, where sound plays the most prominent role, eliciting intellectual discoveries through immersion into that world with which she fell in love, and finding “creative ways to show the sounds through image.” She poured over countless hours of archive footage to select the perfect soundbites, experimenting with the lighting until it matched the frequency of the camera and sound. This created a wavelike, underwater effect, unconventionally transforming the space to give the sound an interesting visual platform through which to breathe. The film took four years to make, so to win Best Feature after such a journey certainly made the endeavor worth the effort.

While Speak So I Can See You is impressive, it does lack a certain emotional quality. That was not the case with the winner of The Witold Sobociński Award for Best Cinematography, Tamaran Hill (Tadasuke Kotani, Japan, 2019). My personal choice for Best Film and clearly inspired by Yasujiro Ozu’s films, this was one of the most sophisticated films I saw in the festival. Tadasuke combines the intricate, excruciatingly detailed narrative of how Tamaran Hill came into existence, with the protagonist’s heart-breaking personal story of discovering her own past, performed with gorgeous melancholy by Hinako Watanabe. Although the film is a very slow-burning piece of quiet contemplation, Tadasuke beautifully explores how this innocuous location is teeming with history. It makes one wonder what fascinating stories are contained within any street, and what other films might capture that visceral connection to one’s home.

In addition to feature films, there were also an incredible number of short films, with many the result of a competition in St Andrews. The winner of The Saint Andrew Award for Best Film – as well as The Alexander Mackendrick Award for Best Director, and my personal favorite from the festival – is one that touches on similar themes to Tamaran Hill. The Back-Flow Rain (Yang Yudan, China, 2021) is about a girl in search of her mother, alongside a legend about rain falling upward every summer solstice. You know a film is going to be amazing when it starts with a long take utilizing a wide range of techniques to shift the speed, location, focus, and color palette without ever cutting. The quality of the filmmaking never decreases throughout its modest half-hour runtime, with intensifying emotions through the superb performances of the two Zhangs, poignant dialogue, and melancholic rumination. In her acceptance speech, Yang said she felt the film was immature. Yet nothing could be further from the truth, because despite being her debut, she displays a beautiful proficiency in the camera, with a screenplay laced with mature sorrow. If this is a sign of things to come, then I predict she will soon become a much more widely recognized filmmaker. I certainly cannot wait to see what she makes next.

Every film at the festival was available to stream straight from the website with no set schedule. Although that ease of access allowed me to watch as much as I wanted rather than could, it does detract from the viewing experience. That is what made the closing film, Man of God (Yelena Popovic, Greece, 2021) – the winner of The Živojin Pavlović Award for Best Director and the audience pick for Best Feature – so special, having been promoted throughout the week ahead of its UK premiere. This is a film with an immense impact and Popovic demonstrates her directorial prowess with excellent framing and a brilliant ability to draw out the right emotions from each scene. The washed-out color palette may be off-putting to some, but she still managed to elevate the otherwise gray aesthetic with some lovely cinematography. Popovic stressed in the Q&A how she “needed people that, without saying a word, it would be believable they were portraying the characters they were playing.” This might seem obvious, but she succeeds in giving her world a level of believability that is surprisingly difficult to achieve. All her actors inhabit their characters flawlessly, so that even when their actions and words are kept to a minimum, their screen presence never falters. Chief among them is Aris Servetalis, who is fantastic in his role as Saint Nektarios, giving an immensely complex performance as his piety is tested, culminating in a beautiful death. I love films that grapple with faith and unjust persecution, and Man of God is an outstanding work, demonstrating that just because Nektarios was a saint does not mean that the strife he faces is unrelatable. As Popovic made sure to clarify: “I never intended to make a religious film… I was focusing on the human level of the story.” She spoke about how much his story spoke to her, as the existential crisis she was going through while in Greece stemmed from a similar personal turmoil. That emotional core certainly shines through and is no doubt what has allowed Man of God to become so popular. Although I have only touched on a handful of the films presented at the festival, there were many more that were likewise incredible: for example, Est (Antonio Pisu, Italy, 2020), an Italian political thriller road trip comedy that won The Suso Cecchi d’Amico Award for Best Dramaturgy and a triple Ralph Richardson Award for Best Actor; also The Parcel (Indrasis Acharya, India, 2019), which despite not winning any awards, was a strong, subversive drama from India; as well as Seeking Glass (Charles Scott, Scotland, 2021), a film that might not have had the best screenplay, but more than made up for it with its gorgeous candlelit aesthetic; not to mention the wealth of animated films that populated the program, from the artistically powerful Homebird (Ewa Smyk, UK, 2021) to the charming 3D animation of Build Me Up (Steve Lawson, UK, 2021). SAFF 2021 was an immense success, due in no small part to the diversity of the selection – in genre and style, but also culture and background – in the program curated by Mina Radović. It is inspiring that in only its third year it has been able to bring together such phenomenal talent, from first-time directors to veteran filmmakers. As the festival’s cofounder, Boris Bosilkov, said during the award ceremony, his vision is to “build a platform that would be the centre for independent filmmakers around the globe.” Independent filmmaking is a difficult endeavor and the rewards do not always speak for themselves, but if everyone who helped bring SAFF 2021 to life continues such splendid work, Boris’s dream may very well become a reality.

Author Biography

Ash Johann is an Anglo-Cuban filmmaker, studying film at the University of St Andrews. Originally training as an actor in a variety of youth theaters, he decided to switch to film criticism. He is now a cofounder of Amaurea Creative Productions, frequently authoring articles on cinema.