A young boy is waiting with his mother in a hospital room as muffled noises overshadow the doctor’s examination. The audience is deprived of any sense of sound or space. Only once the two leave the hospital do we hear the first line of dialogue: “You’re an embarrassment.” An opening both visceral as it is obscure, Kalel, 15 (Lana, 2019) instinctively challenges its audience on both a visual and narrative level through its first spoken scene. With Kalel’s mother threatening her son to not tell anyone about his diagnosis, her ensuing use of vulgar, impulsive language (“You better not tell your sister. Her tongue is loose, like her vagina”) instantaneously sets the tone of the film: an uncensored, stark, and unapologetically honest portrayal of the volatile relationship between a single mother and her teenage children. Most importantly, as Lana subsequently cuts to Kalel’s exploration of his sexuality and erotic capital via social media, these successive opening shots solidify the film’s most intriguing thematic elements: youth, sexual desire, rebellion, belonging, and companionship.

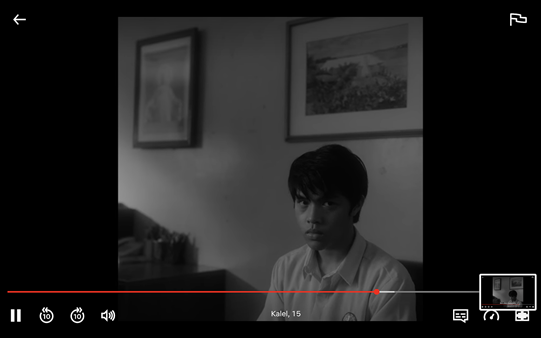

What remains the most interesting in Lana’s film, however, is that the aforementioned themes circle around one single, conflicting idea: religion. This is embodied through Kalel’s biological father (a priest), Kalel’s Catholic schoolteachers, and the film’s own mise-en-scène, imbued with religious symbolism. In a Southeast Asian country as strictly Catholic as the Philippines, the conundrum of Kalel’s HIV diagnosis ultimately incites a tense, complex relationship between faith and infidelity. As such, Lana’s depiction of profanity, disrespect, and ignorance amongst Kalel’s family and friends powerfully emphasizes this particular polarity of societal obedience versus sexual freedom. Once Kalel’s mother asks her son “What will other people think?” it becomes clear that Kalel’s HIV diagnosis is equated to public rejection for both him and his family. We see this dilemma slowly unfold through Kalel’s suffocating loneliness as he navigates his social and academic life while hiding his diagnosis. To achieve this poignant, interior perspective, the film heavily rests upon the performance of its protagonist, convincingly portrayed by Elijah Canlas. By exploring this delicate topic with emotional depth and realism through the eyes of a 15-year-old, Canlas is able to near flawlessly capture this internal unrest, oftentimes with mute subtlety. As such, the authenticity of a teenager experiencing love, sexuality, alienation, and peer pressure is effectively brought to life, enabling the audience to share every moment of hesitation, rejection, fear, and pain expressed by Kalel in that exact moment on-screen.

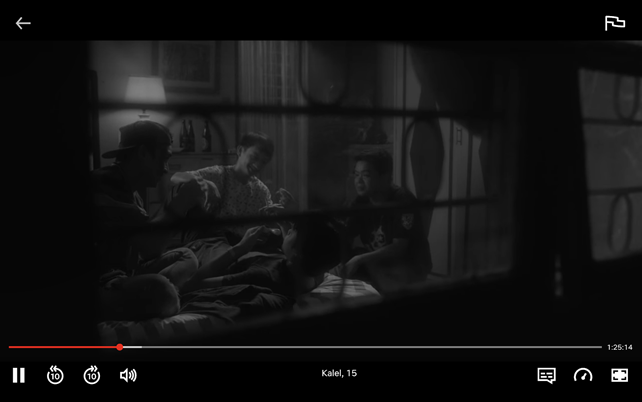

However, this introspection also remains powerfully strengthened by the film’s cinematography. The beauty of Kalel, 15 – particularly its monochromatic symmetry – is simply hard to ignore. Lana’s black and white cinematography infuses the film with a sense of desperation, visualizing Kalel’s emotional and physical struggle. It also captures the redundancy of what it is to live an underprivileged, domestic life in the Philippines. With many of the scenes filmed through wooden window blinds (a common characteristic of a typical Filipino household), not only does Lana establish an intimate sense of space, but it is as if the film invites us to closely peek inside every layer of Kalel’s life. We attentively follow each step, conversation, fight, and confession from various angles. Thus, as the audience seemingly shares this intimate, private space with our protagonist, Lana establishes a uniquely personal, emotive relationship between the characters, their environment, and the spectator. The cinematography becomes as layered and striking as the film’s thematic complexity and the emotional weight carried by its protagonist, as each frame mirrors the instability of Kalel’s strained relationship with his family and friends.

Worth mentioning is also the scene in which Kalel and his friends try drugs for the first time. Here, Lana’s use of slow-motion perfectly captures the essence of what it is like to live the life of a teenage boy – a stylistic achievement reinforcing the film’s authentic, youthful touch. Narratively speaking, however, it is precisely within this moment of recklessness and vulnerability that Kalel suddenly confesses his HIV diagnosis, thus shifting the film into a disastrous, emotional cascade of events. Hence, while Lana authentically captures the congenial spaces of teenagers who are smoking, dancing, and getting high, these culminating scenes also become the catalyst to Kalel’s destruction.

Following this narrative shift as Kalel’s diagnosis spreads amongst the community, the film’s most interesting stylistic feature occurs: its change in aspect ratio. After Kalel is told by the doctor that HIV can spread through blood transmission, this stark realization is sharply echoed within the cinematography itself. With the conventional 4:3 ratio now concentrated into a single square, Lana not only establishes a more intimate focus on Kalel, but signals an emotional intensity as Kalel is soon left abandoned and deserted by those around him. As the camera shakily moves with our broken protagonist, seemingly reflecting his sudden aimlessness, the small frame amplifies how Kalel is left to fend for himself, both physically and emotionally. After all, once his mother leaves, his sister is imprisoned and he is evicted from his home, the small screen – now dominated by an overwhelming blackness – depicts Kalel in a fetal position. Left on the brink of starvation with only a small candle for light and a cardboard box to lay on, Lana powerfully illustrates the depths of this lack of support system, and the mental destruction it will leave on our protagonist. Kalel, in an act of desperation, seeks help from his father, who agrees to help his son yet refuses to pay bail for his imprisoned sister. Kalel’s father coldheartedly explains: “Kalel, your sister is not my responsibility. She’s not my child.” Thus, his father’s unwillingness to help his sister not only reinforces the instability and neglect of Kalel’s surroundings, but allows Lana to touch upon the fickleness of religion itself. It is shown to be not as overtly faithful as initially believed, when even a priest – a figure of trust and benevolence – may act in selfish ways. Nonetheless, after retrieving the money from his father, Kalel spits on a glass coffin of Jesus in a church, before the screen abruptly cuts to black. By showcasing the desperation and anger raging inside our neglected protagonist, Lana thereby reinforces how the notion of religion remains a pivotal core anchoring the film’s duality between faith and Kalel, the carrier of a sexually transmitted disease.

Conclusively, then, Lana manages to simultaneously capture the insecurity, emotional loneliness, complexity, weight, and sexual desperation of his protagonist. The fact that the origin of Kalel’s diagnosis is never directly addressed lends the film a sympathetic edge, whereby the individual, rather than the disease, remains at the forefront. As such, Lana’s nuanced and careful introspection from Kalel’s perspective – the exploration of his inner turmoil – allows the film to portray a raw and intimate insight into the life of a young Filipino boy struggling with his sexual identity and the loss of his family and friends as a result of his diagnosis.

Author Biography

Vanessa Zarm is a recent graduate of Queen Mary University of London; her interests lie within contemporary issues of mainstream film, including the growing role of social media bleeding into contemporary cinema. She plans on further pursuing these research interests through postgraduate studies.

Film Details

Kalel, 15 (2019)

Philippines

Director Jun Lana

Runtime 104 minutes