“People change, feelings change, but that doesn’t mean that the love once shared wasn’t true and real. It simply means that sometimes when people grow, they grow apart” (We Broke Up).

For the past twenty-thirty years, girls all over the world have fallen under the idealization of romantic comedies, commonly referred to as “rom-coms.” These films usually follow a fairly predictable plotline: guy meets girl, guy becomes attracted to girl, an obstacle stands in the way of their love, and finally, all barriers are broken for them to be together forever. In all of these films, the viewer takes away a universal message: love prevails. Love can (and will) defy all odds for the two main characters (usually a heterosexual couple) to live happily ever after no matter the outside circumstances. But I’d like to present a bit of a different storyline that exists right on the line of the rom-com genre, one that recognizes the value in a fleeting love, a love that you cannot realistically hold onto forever—a genre I have labeled the anti-rom-com.

As a now twenty-one-year-old who became obsessed with traditional rom-coms around the age of twelve, I have admittedly developed unrealistic expectations of love and relationships. Now don’t get me wrong, I think realistic expectations and high standards can most definitely coexist. I am a strong advocate for high standards, knowing what you deserve, and not settling for anything less. So while I will never pursue a relationship with a man who doesn’t tip the waitstaff or yells at his mother (high standards), I will hopefully understand when love just isn’t enough to keep an expired relationship alive (realistic expectations). I like to think I’m a hopeful romantic who recognizes that life still keeps moving despite the idealized vision of a “perfect” love that I can create in my mind.

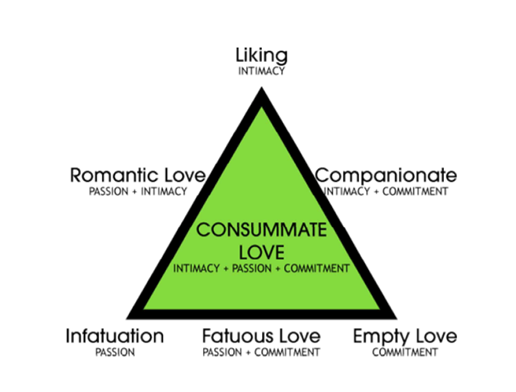

I will be the first to admit that love is a terribly loaded word. A word with hundreds of different meanings, interpretations, and uses. The love that I will most often be referring to is a romantic love that includes two distinct features: intimacy and passion. If a third piece is added, commitment, then this romantic love can take on a new title, consummate love (see Figure 1). In a 2016 article published by The Polish Journal of Aesthetics, Sheryl Tuttle Ross argued that modern philosophical ideas can lead to “the view that modern marriage as a social institution requires monogamy and lifetime commitment to one’s beloved and, moreover, that being married is one of life’s great accomplishments” (151). But with a shattering of these modern philosophical ideas, I am here to argue that consummate love might not be the end-all-be-all, so why is it so often presented as such?

In Marc Webb’s 500 Days of Summer (2009), Tom (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), falls head-over-heels for the new girl at work, Summer (Zooey Deschanel). Summer and Tom develop an intense emotional connection, naturally leading Tom to want to enter into a committed, romantic relationship with her. He envisions what their life could look like, the children they could have, and the future they could build. But Summer isn’t so keen on the idea of commitment, or at least a commitment to Tom. Normal narratives of love and relationships are broken as the expected chronological timeline itself is shattered, the entire story told in reverse chronology starting at day 500 of their relationship. A postmodern aspect of cinema is introduced in two distinct categories: narrative structure and plot structure, knowing that “philosophical meanings are postmodern if they challenge what is accepted as obvious by modern thinkers or ideas accepted as commonplace” (Ross 151). The viewer may leave the film with a feeling of confusion or sadness, because the two main characters never experienced consummate love (intimacy, passion, and commitment), only romantic love (intimacy and passion).

Similar ideas are introduced in films like Nikole Beckwith’s Together Together (2021) and Jeff Rosenburg’s We Broke Up (2021). In Together Together, Matt (Ed Helms), a 40-something single man, obtains a surrogate, Anna (Patti Harrison), to birth his biological baby. Throughout the entire film, the viewer is led to believe that the two will end up in some form of a romantic relationship before the credits roll. So when the final scene is Anna birthing Ed’s child with no kiss shared or “I love you” exchanged, the viewer wonders what went wrong. Well, nothing went wrong. The two just weren’t meant to fall in love in the way we expected. And in We Broke Up, recent exes must pretend to still be together at a wedding, even though they feel as if their love has expired. This isn’t a sign of defeat or failure, although their family and friends may view it as such. The two simply realized that they grew apart and in vastly different directions, and there was no point in holding onto something that just didn’t serve either of them well anymore. Love didn’t prevail, and that was okay.

Traditional rom-coms have only furthered the idea that women need to be in a relationship to find meaning, perpetuating stereotypes that should have died out years ago. Young women should have full agency to choose—without backlash from family, friends or society in general—whether or not they want to enter into a committed, romantic relationship. I’m not spreading the message that women should remain single their entire lives in an effort to dismantle the patriarchal foundation that our country was built on; I’m simply presenting the idea that our society needs to stop viewing marriage as the end-all-be-all. Life is made up of love that manifests in hundreds of forms, not just that found with a romantic partner. If you happen to find it somewhere throughout the course of your life, great! But if you don’t, there’s nothing wrong with you. Your life still holds incredible meaning and value without a partner attached to it.

Author Biography

Katharine Chapin lives in Wilmington, NC, with her best friend/roommate, Rita. She begs for permission to bring home a dog daily, but is consistently shot down for very logical reasons. So instead of finding joy through a puppy, she spends her time reading predictable romance novels, watching low-budget indie films, and overanalyzing every minor detail of her life. She hopes to live in Boston to pursue a career in media/film after college.

References

“500 Days of Summer.” [FILMGRAB], 7 Aug. 2019, https://film-grab.com/2016/11/01/500-days-of-summer/#bwg471/28835. Accessed 27 Nov. 2021.

Ross, Sheryl Tuttle. “500 Days of Summer: A Postmodern Romantic Comedy?” The Polish Journal of Aesthetics, no. 41, 2016, pp. 155-175. https://pjaesthetics.uj.edu.pl/documents/138618288/138826957/eik_41_8.pdf/f6dbe6d6-9411-43f3-8fb5-2830876b1f46. Accessed 19 Nov. 2021.

Sternberg, R. J. “A Triangular Theory of Love.” Psychological Review, vol. 93, 1986, pp. 119-135.

Filmography

500 Days of Summer. Dir. Marc Webb. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2009.

Together Together. Dir. Nikole Beckwith. Hulu, 2021.

We Broke Up. Dir. Jeff Rosenburg. Hulu, 2021.