After his father dies in a fire, Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield) is taken in by his Uncle Claude (Ray Winston), who takes care of the clocks at a train station. Claude is a drunk and eventually disappears, leaving Hugo to fend for himself. The only things that Hugo has from his previous life are an automaton that his father found in the attic at the museum where he worked and the notebook that his father kept as they were trying to repair the automaton. To prevent losing his home, Hugo continues working on the clocks on his own. He also continues trying to repair the automaton using parts that he pilfers and steals. It’s while stealing parts from a toy booth at the station that he meets the other main character, Georges (Ben Kingsley). Georges has caught Hugo in the act of stealing and, during the subsequent shakedown, discovers the aforementioned notebook. Georges is shocked by the drawings found within and, after Hugo refuses to say who drew them, takes the notebook, saying that he will burn it. Hugo follows Georges home to get the notebook back and meets Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), who lives with Georges and his wife Jeanne (Helen McCrory). The two become friends and bond over a shared love of the movies. At one point, Hugo discovers a key that Isabelle has around her neck in the shape of a heart. He realizes that the key would fit in a slot on the automaton. Hugo and Isabelle use the key, and the automaton comes to life. Hugo believes that the automaton will write a message from his father. Instead, it draws the famous image from Georges Méliès’s Le Voyage dans la Lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902) and signs the image Georges Méliès. Isabelle explains that Georges’s full name is Georges Méliès. This eventually leads them to Rene Tabard (Michael Stuhlbarg), a historian and fan of Georges Méliès’s films. He travels to Georges’s home and plays one of his films for Jeanne, Hugo, and Isabelle. Georges returns home at this time and, after encouragement from his wife and the others, tells the story of how his career as a filmmaker ended. He also mentions that he believed the automaton he created had been destroyed in the fire that killed Hugo’s father. Hugo leaves to get the automaton but is captured by the station inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen). The inspector is getting ready to take Hugo to jail when Georges shows up and tells the inspector that Hugo is his boy. The film ends with a public presentation of Georges’s films and an after-party where all the various characters celebrate Georges’s accomplishments.

Setting, Décor, and Properties

Setting

Hugo takes place in Paris, France, in the year 1931 (Figure 1). This makes sense because, while the story presented in Hugo is fiction, the characters of Georges Méliès and Jehanne d’Alcy are real people. In fact, the base story of how Méliès came to be where he is at the beginning of this film is true. He was financially ruined, and he did work in a toy stand in the main hall of Gare Montparnasse, a railway terminal in Paris, France (Campsie). Martin Scorsese and his production designer created elaborate sets to represent key locations in Méliès’s life, such as the train station, his home, and even his famous glass film studio that we see in flashbacks. While they may not be perfect replicas of the originals, they are excruciatingly detailed and completely faithful to the period.

Décor

Nearly as important as the settings is the décor that inhabits them. It’s no small feat to recreate 1930s Paris. The world must look real; it must look lived in. Scorsese and his crew achieved this in incredible detail. One could pick out any frame in this movie, and it would be full of items that are all period-appropriate. A perfect example of this is the scene at Georges’s toy booth (Figure 2). In it, we see a side view of the counter and Méliès’s toy counter. Aside from the space immediately in front of Méliès and Hugo, the counter and walls are entirely covered with toys and other knickknacks. All of the toys are appropriate to the period and look as if they’ve spent many years being loved and played with by a child. There’s so much detail that could be missed by a casual viewing. In fact, once I had stopped at this moment, I spent some time just exploring the space and studying the different items. It reminded me so much of the old I Spy hidden items books that I used to look at when I was a child in the 1990s.

Props

There are quite a few items in this film that are narratively important as they help connect our main character, Hugo, with Georges Méliès and reveal Georges’s true identity. Hugo’s father’s notebook, Mama Jeanne’s heart-shaped key, and Méliès’s drawings in the box on top of the wardrobe are all clues that lead the main character on his journey of discovery. The most essential props in the film are also the ones that are most visually arresting. These are the automaton and drawing that it creates, which ultimately connects the automaton with Méliès and leads Hugo to discover Méliès’s past (Figures 3 and 4). I found this prop so interesting that I did some research into its making. I expected it to be at least partially computer-generated. I certainly expected the process of creating the drawing to be artifice. I was wrong. It turns out that the automaton was created by famous prop maker Dick George and was completely real. Even more surprising, the automaton actually draws the entire picture. (Figure 4). According to George, it takes “46 or 47 minutes” to complete the whole image (Lytal).

Lighting

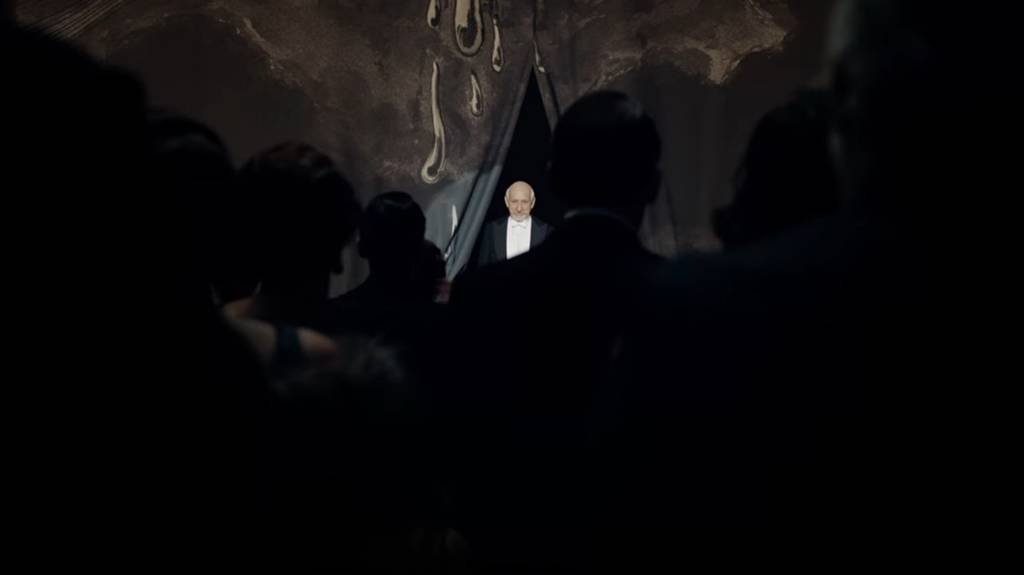

Like most films, lighting is used in Hugo for a variety of purposes. Most of the time, the lighting is meant to seem completely practical, having come from various sources on the screen, such as overhead lamps, wall lamps, or streetlamps. One of the fantastic things that Scorsese does in this film is use lighting to help the audience feel the atmosphere that our character is in. An excellent example of this would be when Hugo and Isabelle meet for the first time outside of Georges’s house (Figure 5). The characters are standing in pools of yellow/orange light being cast by street lamps or through the door of the home. The cityscape that we see behind and around the characters is dark and lighted in blue hues. This lighting choice, coupled with the visible snow in the scene, gives the scene a cold feeling. The orange-hued light from the house door and window says to us that the home is warm and inviting. Another way that lighting is used in this film is to separate characters from their surroundings. A perfect example would be the scene at the end of the film when Georges is onstage introducing his film (Figure 6). In this scene, Georges is bathed in light while the audience is cast almost wholly in shadow. This is important because it’s the moment where the character is finally being appreciated for his work. Georges is suddenly thrust into the literal and figurative spotlight.

Costume, Makeup, and Hairstyles

Costume

As this is a period movie, how the characters look is very important. The costume department clearly put a lot of time and effort into creating an exhaustive variety of costumes for not just the main characters but all of the extras. The film is set in 1931, so the costumes are a good mix of the 1920s- and 30s-era styles. The best scenes to see this variety are those in the train station (Figure 7). We see hats such as cloches and bowlers mixed with Trilby hats and even some stereotypical French berets. Women are seen in day and formal dresses frequently worn during the period, while men are generally seen wearing suits. Aside from indicating the period that the film is taking place in, the costumes are also used effectively to indicate the status and class of the characters in the film. This is especially noticeable with the main character Hugo. For much of the film, Hugo wears the same outfit. A sweater with a collared shirt covered with what looks to be a tweed jacket. Despite the cold, he’s wearing shorts with shin-high socks and shoes that are worn out. His skin and outfit are dirty (Figure 8). In the flashback scenes, when he still has his father, Hugo’s clothing is cleaned and well kept, with no dirt to be seen. Interestingly, in the last flashback, when his uncle comes to get him after his father dies, we see Hugo is wearing the same sweater and shirt that he wears throughout the film, except that it’s clean and looks new (Figure 9). This was a conscious decision by costume designer Sandy Powell. In an interview published in Children & Libraries, Brian Selznick, the author of the book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, noted that “her idea was that Hugo, having moved to the train station quite suddenly, didn’t bring any clothing. So he’s still in the clothing he brought with him, and everything is getting small on him. His sleeves are halfway up his arms and his pants are too short” (Brown).

Makeup

As with many period films, the makeup is understated. All main characters throughout the film had no obvious makeup, and they look completely natural. This is intentional as the characters that we see are not meant to be upper class. The one exception to this, again, is from one of the flashbacks. In the scene toward the end when Georges tells his story, we see Mama Jeanne as a performer in Georges’s magic show (Figure 10). In it, she’s wearing what would be, for the time, garish eyeliner and eyeshadow with red and silver rhinestones glued to the points of her eye. She’s also wearing bright red lipstick. This is appropriate because of both the period being represented and the fact that she’s a stage performer.

Hairstyles

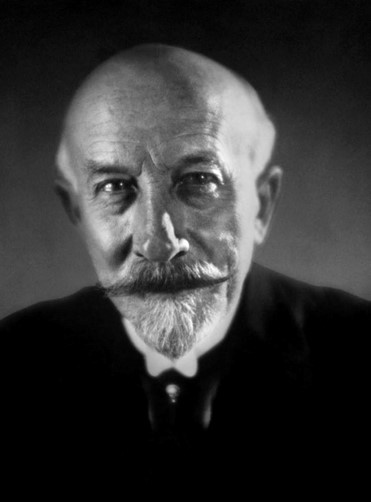

Hairstyles, like costume, are used to show the time period that the film is taking place in. Women in the film are frequently seen with 1920s-style bobs (Figure 11). Men’s hairstyles are universally unassuming and often hidden by hats. Where men shine is in their facial hair. A perfect example of this would be Georges himself. His had a practical source as it was the style of facial hair worn by the real Georges Méliès in every picture that we see of him (Figures 12 and 13). While many men in the film are clean-shaven, beards and handlebar mustaches are much in evidence.

I clearly remember seeing Hugo for the first time in theaters and being blown away. I loved the story, which touched on the history of early cinema in an almost meta way. While I wasn’t studying film at the time, it was still something that I was passionate about. I also was astonished by all of the detail in the film. At the time, I had no understanding of mise-en-scène or the role it played in movies, but I could still appreciate the different aspects that make up mise-en-scène. I loved the look and feel of this movie. Scorsese uses lighting so effectively that you almost feel the cold when we are outside in snowy Paris, and we feel the warmth when we are inside and out of the cold. He engrosses us in this fantastical story by expertly using props such as the automaton to tie the different narrative elements together. Finally, he captures the age of the film through the expert use of decor, costumes, hair, and makeup. Every item in the film looks like it was plucked out of a 1920s or 30s photograph and every character down to the lowliest extra perfectly represents the period in which the film takes place. In short, the use of mise-en-scène in this film is masterful.

Author Biography

Dan Verley is a third-year student at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. He is currently working toward a bachelor’s degree in Film Studies. He hopes to contribute to the art of film both through his study and commentary of film as well as creatively as a narrative filmmaker.

References

Brown, Jennifer M. “Hugo Cabret, from Page to Screen.” Children & Libraries, vol. 11, no. 1, 2013, pp. 35-38. ProQuest, https://search-proquest-com.liblink.uncw.edu/scholarly-journals/hugo-cabret-page-screen/docview/1353653314/se-2?accountid=14606. Accessed 02 May 2021.

Campbell, Carolyn. “Georges Méliès.” City of Immortals, 21 Jan. 2018, cityofimmortals.com/georges-melies/. Accessed 02 May 2021.

Campsie, Philippa. “Discovery in a Dairy Shed.” Parisian Fields, 23 July 2016, parisianfields.com/2012/01/01/discovery-in-a-dairy-shed/. Accessed 02 May 2021.

Lytal, Cristy. “Working Hollywood: Dick George, Prop Maker.” Los Angeles Times, 27 Nov. 2011, www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-xpm-2011-nov-27-la-ca-working-hollywood-20111127-story.html. Accessed 02 May 2021.

Film Details

Hugo (2011)

USA

Director Martin Scorsese

Runtime 126 minutes