Director, Henry Selick, routinely utilizes stop motion to seamlessly relay critical themes and motifs while supporting his cinematic content. Selick demonstrates his influence and artistic control via stark color contrasts, similar themes, and dark cinematic concepts across each of his films, including James and the Giant Peach (1996) and The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), among others. The director adopts a similar strategy in his 2009 film Coraline, based on Neil Gaiman’s book of the same name. Through an array of visual motifs, director of Coraline, Selick, delivers a cautionary tale encouraging viewers to relinquish envy and find contentment in their lives.

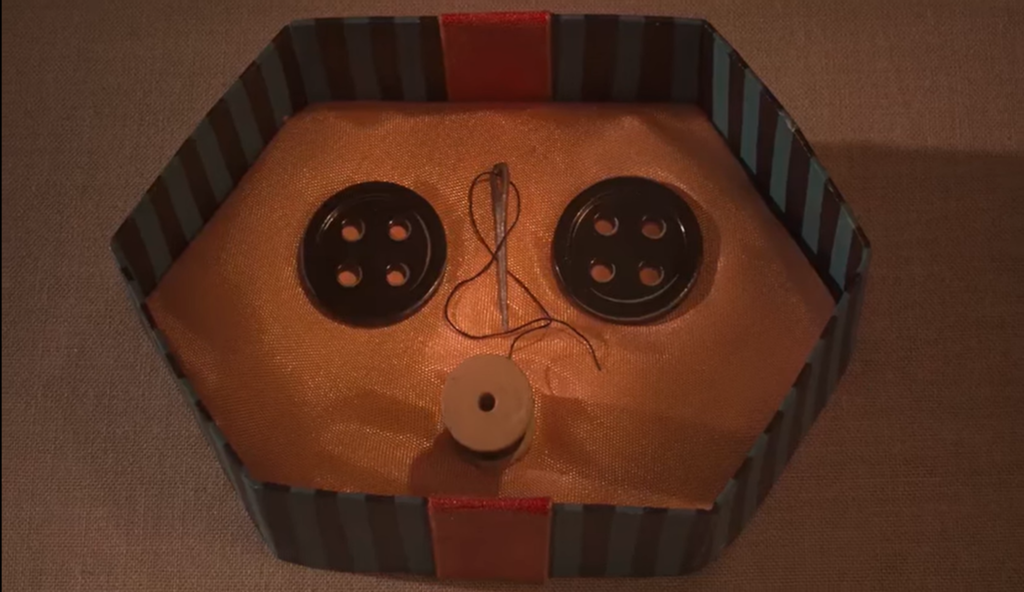

Early on in the film, Selick presents viewers with props that evolve into visual motifs throughout the movie. The first notable motif the director introduces is the Coraline doll. Wybie, the only other child that resides in the neighborhood, gives it to Coraline, claiming that he merely found it. Selick makes evident the peculiar nature of the claim and the doll itself by making the doll identical to Coraline – except for the buttons where its eyes should be. The motif is representative of what the Other Mother intends Coraline to become – silent and conforming. Many scenes feature shots of the doll in various locations spying on Coraline as she explores in the foreground. Between the irrefutable resemblance it has to Coraline and how it practically lurks in the background, the doll maintains something of an eerie presence. Though the doll may initially present itself as unremarkable, in reality, it serves as yet another tool of the Other Mother’s making, one used to manipulate Coraline.

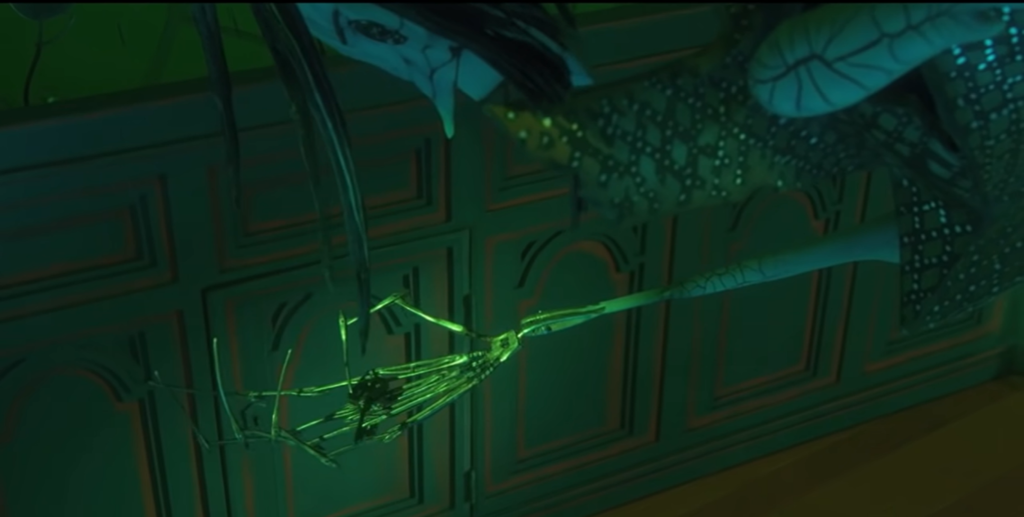

Another visual motif prevalent in the film is the key. Selick introduces the key into the story world’s framework and ensures that it circulates throughout the film to draw attention to its importance. The key serves as a gateway to the other world and escapism for Coraline, just as it was for the Other Mother’s previous victims. Though Selick meets success by deviating from the tropes and conventions often found in horror films, he also adheres to some of them. Polanski, for instance, explores similar contexts in his films. “Filmmaker, Roman Polanski, has established himself as a master of horror film through his highly influential and highly controversial ‘Apartment Trilogy'” (Davies 18). In Polanski’s films, the protagonists’ horrors occur within their home.

Similarly, the nightmarish incidences that Coraline experiences occur almost entirely in her home, whether it be the home located in her world or the other world. Although there is only one key, the Other Mother ensures it is always within Coraline’s grasp so that Coraline may easily enter the world, thus making her vulnerable. Coraline’s vulnerability routinely leaves her susceptible to death at the hands of the Other Mother. At the film’s conclusion, amidst Coraline’s desperate attempt to reclaim and dispose of the key, Selick indicates that the key’s destruction is the only way to defeat the Other Mother and prevent her from escaping her world or claiming more victims.

Arguably, one of the most pertinent visual motifs evident in Coraline are the buttons. Coraline does not get the opportunity to frequent the other world for long before the Other Mother attempts to strike a deal. Coraline must get the buttons sewn in her eyes in exchange for the treats and attention the Other Mother offers her – a proposal Coraline quickly turns down. Via the button motif, the director indicates that what one wants often comes at a price. The main characters that have a notable influence in Coraline’s life each have a doppelgänger – all of which have buttons for eyes, much like the Coraline doll. The buttons are the first significant indication of deception that Selick introduces in the film. Often, eyes are deemed the windows, so to speak, to the soul, as they reveal one’s emotional state, despite their adopted façade. Given that the Other Mother, like her minions, has buttons instead of eyes, Coraline and viewers are left susceptible to deception throughout the film’s duration.

Director of Coraline, Henry Selick, strategically introduces a series of motifs throughout the film. Although the motifs serve various purposes, the director predominately depicts them to inform the cinematic content. Selick’s visual motifs reflect the danger that accompanies envy. In doing so, Coraline serves as a cautionary tale that encourages its intended audience, children, to beware of strangers, forfeit their envy, and extend gratitude to the positive relationships and luxuries in their lives.

Author Biography

Tia M. Adkins is an aspiring screenwriter actively pursuing her undergraduate degree in film studies at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. She’s an impassioned storyteller, fitness fanatic, and corny jokes enthusiast. When she’s not reading, writing, or watching her favorite movies and TV shows, she’s expanding her ever-growing Funko POP! Figure collection.

Reference

Davies, Rob. “Female Paranoia: The Psychological Horror of Roman Polanski.” Film Matters, vol. 5, no. 2, 2014, pp. 18–23.