One of the most influential films in cinematic history, Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 science fiction masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, is as mysterious as it is inspiring. Who can forget the amazing shots of space shuttles flying peacefully through the cosmos accompanied by beautiful classical music? Nobody had seen anything like it before and we still haven’t seen anything like it since. One element of this film that makes it so powerful is the reoccurring motif of ninety-degree angles that can be seen in its props, set designs, and cinematography. There have been many analyses and interpretations of 2001 but, to this day, Kubrick and writer Author C. Clarke have made critics and viewers scratch their heads over what the film really means, and have influenced us subliminally with this ninety-degree-angle motif through props, set designs, and specific camera movements and placements.

During the “Dawn of Man” sequence at the beginning of 2001, we see desolate landscapes with apes eating grass and running from predators. Suddenly, the black monolith appears, and the apes cautiously examine it by putting their hands on it. The next shot we see is the monolith as it aligns with the sun and the moon with the camera placed at the bottom looking straight up, creating a ninety-degree angle from the ground (Figure 2). Like a rocket about to be shot off into space, Kubrick positions the camera in a unique way that instills wonder, curiosity, and fear in the viewers.

Figure 2. Camera aligns with the sun and moon from the bottom of the monolith

in 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM, 1968); 11:31

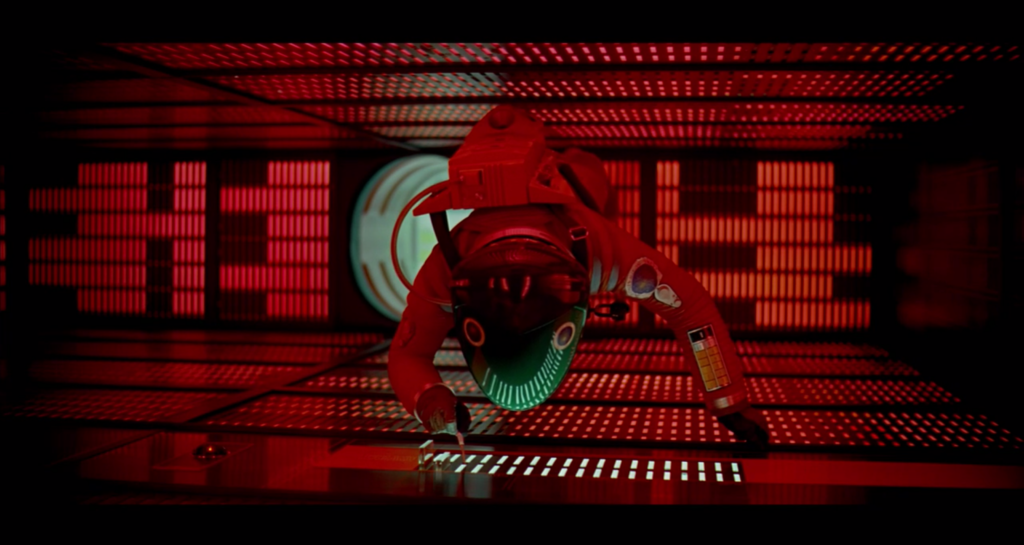

In the scene where the supercomputer HAL-9000 is introduced, astronauts Dave Bowman (Kier Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) watch an interview of themselves on rectangular devices that looks strikingly similar to modern-day tablets. They watch the interview with the length of the screens in a vertical position, unlike the horizontal positioning we are used to (keep this in mind as we will explore a popular interpretation of the monolith and the film as a whole in the following paragraphs). While watching the interview the two astronauts eat their meals out of trays that are rectangular in shape and the camera placement of these shots is at a ninety-degree angle from where Dave and Frank are sitting (Figure 3). Even the film’s antagonist, HAL-9000, is in the shape of a rectangle.

Figure 3. Medium shot of Dave Bowman as he watches himself from a ninety-degree angle

in 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM, 1968); 56:37

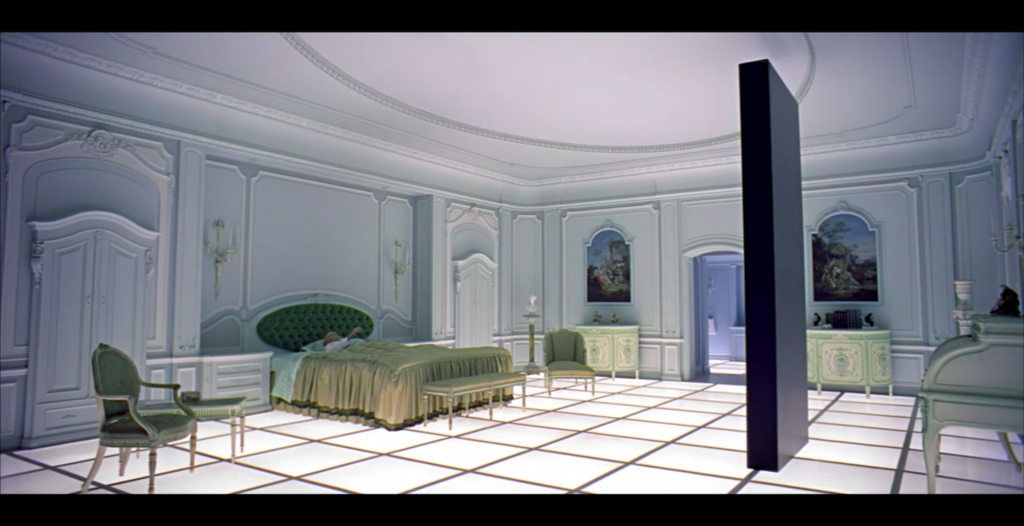

Later in the film, Bowman enters the circuit room where HAL’s memory is stored and deactivates him. The room is literally a hollowed-out rectangle filled with even more rectangles that makeup the HAL computer. For most of the shots in this scene, the camera looks down at him from the top, once again, ninety degrees from the character’s perspective (Figure 4). Other props and set designs featuring this ninety-degree motif are buttons in the escape pods, the landing pads for space shuttles, hallway designs, and many of the shots during the “Stargate”sequence. These examples just scratch the surface of the ninety-degree-angle motif that is within 2001.

Figure 4. Long shot of Bowman deactivating HAL inside a rectangular room

in 2001: A Space Odyssey (MGM, 1968); 1:49:13

At the beginning of the film when the apes make contact with the monolith, this shows the first time a creature on Earth has ever touched something with a ninety-degree angle, in the context of the film. Afterward, a series of actions is set in motion. The apes learn that a bone could be used as a weapon to hunt and fight off rival apes. While the monolith’s origin and true purpose in the film remain a mystery, it triggers something in the brains of these apes that causes an evolutionary spark, making them more intelligent. Then, probably the most famous cut in all of cinema history is made when the ape throws the bone in the sky and is graphically matched by a space shuttle, showing how far we’ve come since the apes first touched the monolith. When you look at the image of Bowman eating out of the rectangular trays, notice the camera placement of that shot. Not only does the camera create ninety degrees by the direction it faces in relation to the subjects, but there are also many other instances of how the cinematography generates this ninety-degree-angle motif. For example, during the “Jupiter and the Beyond” segment toward the end of the film, the monolith is seen floating and rotating in between multiple planets that are in alignment with each other. As soon as the monolith rotates ninety degrees, so does the camera, and we are then thrown into the “Stargate” sequence where there are even more references to ninety-degree angles.

Why so many rectangles and ninety-degree angles? One popular theory is that the monolith represents a movie screen. That’s right. In a way, Kubrick puts a mirror to his viewers without us even noticing; it is hidden in plain sight. We stare at rectangles all day in our daily lives, whether it’s our phones, a computer screen, or television, and, by turning our heads ninety degrees when we look at the screen,the monolith is revealed to us. Throughout 2001:A Space Odyssey we constantly see the characters staring into rectangular objects just as we are staring into a rectangular screen. Stanley Kubrick’s film is a masterpiece not only on the surface but also on the multiple layers it creates with this sneaky ninety-degree-angle motif in the mise-en-scene and cinematography. To this day, Kubrick’s 2001:A Space Odyssey remains the alpha and omega of science fiction films and proves what is possible with cinematic technology. It is as if Kubrick himself has touched the black monolith.

Author Biography

Aspiring film director, David Flaherty, was born on June 2, 1988, in Charlotte, North Carolina. He was accepted into the University of North Carolina Wilmington in 2017 to pursue his love and knowledge of filmmaking and has his sights set on graduate school one day. He has a passion for learning, exercising, traveling, and meditates daily. His biggest influences are Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, David Fincher, and Denis Villeneuve.